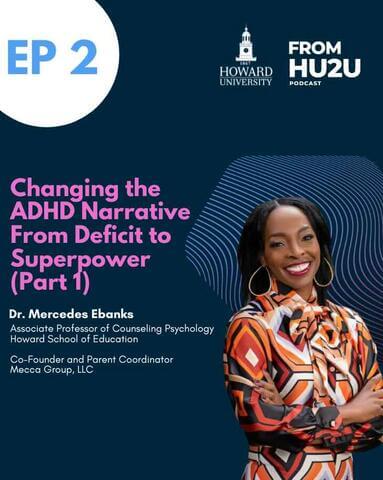

HU2U Podcast: Changing the ADHD Narrative From Deficit to Superpower (Part 1) feat. Dr. Mercedes Ebanks

In This Episode

ADHD is one of the most commonly diagnosed neurodevelopmental conditions for American youth. Addressing the diagnosis is no easy feat, and there is no one size fits all solution. An ADHD diagnosis for Black children can be compounded with unique challenges, such as stigmatization, which can negatively impact how others at school and within their communities treat them.

On today's episode, which is part 1 of a 2-part series, Dr. Mercedes Ebanks joins host, Howard alum, and developmental psychologist Dr. Kweli Zukeri to explore this situation. They will also discuss the potential that lies within changing the ADHD narrative and approach from one of deficit to superpower and how parents and teachers can help their children and students with ADHD both utilize it as a strength and manage its problematic aspects.

Dr. Mercedes Ebanks is a double Howard alum and Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology at the Howard School of Education. She is also a Behavioral Therapist and the Co-Founder and Parent Coordinator of the Mecca Group, LLC.

From HU2U is a production of Howard University and is produced by University FM.

Host: Kweli Zukeri, PhD

Guest: Mercedes Ebanks, PhD

Listen on all major podcast platforms

Title: Changing the ADHD Narrative From Deficit to Superpower (Part 1) feat. Dr. Mercedes Ebanks

Publishing Date: Jul 2, 2024

[00:00:00] Dr. Ebanks: The reality is there is, truly, racial disparities when it comes to diagnosis, treatment, services. Children with ADHD receive services, special education services. However, typically, children that are minority children, Black and Brown youth, typically fall under the category of emotionally disturbed.

[00:00:35] Kweli: ADHD is one of the most commonly diagnosed neurodevelopmental conditions for American youth. Addressing the diagnosis is no easy feat, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. An ADHD diagnosis for Black children can be compounded with unique challenges, such as stigmatization, which can negatively impact how others at school and within their communities treat them. In turn, this may cause them to internalize harmful and debilitating beliefs about themselves, which can have devastating consequences. Despite this, there may also be great potential to be tapped in ADHD for Black children.

On today's episode, which is part one of a two-part series, my guest and I will explore this situation, as well as the potential that lies within changing the ADHD narrative and approach from one of deficit to superpower, and how parents and teachers can help their children and students with ADHD both utilize it as a strength and manage its problematic aspects.

Let's dig into it!

Welcome to HU2U, the podcast where we bring today's important topics and stories from Howard University to you. I'm Dr. Kweli Zukeri, Howard alum and developmental psychologist and today's host. I'm here with Dr. Mercedes Ebanks, Howard alum and associate professor of counseling psychology at Howard's School of Education. She is also a behavioral therapist and the co-founder and parent coordinator of The MECCA Group, LLC.

Peace, Dr. Ebanks! Thanks for joining me today.

[00:02:06] Dr. Ebanks: Thank you for inviting me.

[00:02:11] Kweli: So, let's begin with getting to know you and your background. So, you're a double alum at Howard and longtime faculty member of Howard School of Education in which you've also served as faculty for over 15 years and held various administrative positions. How'd you end up at Howard, and what's kept you here?

[00:02:39] Dr. Ebanks: So, I would say that, first, I was a guest student. I attended Georgetown University. And as a student there, I had a dear friend that attended Howard. And I came to campus often that many thought that I was a student here. So, after I graduated with my degree in psychology, I learned about the programs that Howard had through the school of education, and I applied to the master's program in counseling psychology.

So, I was inspired by the faculty at the school of education. One of my mentors and advisor at the time, Dr. Aaron Stills, encouraged me to pursue my doctorate degree after completing my master's. And then, he also encouraged me to join the faculty as adjunct. And then, eventually, when a position became available, he, along with other faculty at Howard, encouraged me to apply for the position.

I thought I wasn't ready, but they said that I was. So, because of that, the senior faculty really guided me through the process and welcomed me. So, I was really humbled to be amongst the faculty who taught me so many important lessons about culture and behavioral therapy and about education and about the, the need for mental health services for children.

[00:03:57] Kweli: Definitely. At Howard, I hear the common story for people is that the faculty and other people at Howard really inspired them. So, I think that's something I can relate to as well. And it sounds like your education involved not just the schoolwork and getting to know the curriculum, but like a more holistic kind of treatment to, to nurturing you as a student. So, why is it important to you to teach at an HBCU?

[00:04:19] Dr. Ebanks: It's critical. I think that it's the lessons that I learned attending a PWI also was eye-opening, but I think it was more… it evolved more personally, professionally at Howard. I also learned truly that your professional reputation does not start after you graduate. It really starts in the classroom.

So, your relationships with the faculty, how your, your submission of your assignments, your timeliness, the opportunities that you take to get involved in the research, professional organizations as a student, really opens up your path professionally. And that networking is key.

Again, teaching at an HBCU as a Afro-Latina student, I think, really, again, it felt… you know, people say it feels like home, but it feels nurturing. You know, you learn a lot about yourself and how the information truly applies to you and your people and your culture and how you're not only learning about how to work with, you know, people of your same group. You're learning, truly, to work with diverse populations, you know, because again, as Black people, we are not monolithic. So, therefore, we're looking at the different religious groups within our group. We're looking at the different sexual orientations, the different identifications, the different cultures within our group, and not just taking it as a one solution to every single problem.

[00:06:02] Kweli: Certainly. And do you think that kind of lesson or orientation towards teaching you as a faculty member, 15 years later, do you think that's also a part of how you are approaching students now?

[00:06:15] Dr. Ebanks: I certainly give credit to all that came before me in terms of what I do now. I try to replicate it in what I do for my students. I get emails sometimes or messages through, you know, social media that, “Dr. Ebanks, thank you for your support. Thank you for telling me about this opportunity,” or still to this day just sharing information. It's because I got that from, you know, my foundation. My foundation was very strong with the faculty at Howard. And I continue my relationships with the faculty who have now retired. And they're still active in their communities. They're still active in the profession. And that, again, inspires me that I'm never going to retire truly because they haven't.

[00:07:05] Kweli: Right. No, no, I hear you. Yeah, inspired and continue to inspire. That really is, I think, the HBCU tradition. So, that's great to hear. Now, you're also a co-founder and serve as the CFO and parent coordinator at The MECCA Group, LLC, a practice that “provides comprehensive psychological, rehabilitative, and educational services for children, adolescents, young adults, and their support systems.” The service is based in the DMV. Can you tell me about creating and sustaining a mission-driven business as an entrepreneur?

[00:07:35] Dr. Ebanks: Excellent question. Again, I think I was following a path that I did not realize I was on, because again, in high school, people ask you, what do you want to do? What you want to be? And then you go to college and, you know, I was like, “Okay, I'm just going to be a therapist.” But there's so much more within that.

And I did not think that I was going to be a professor. I did not think that I would have my own business. I thought I was going to work in a clinic-based setting, community-based setting providing, you know, mental health services. But there was a larger picture for me. And I believe I was able to follow that, because, again, kind of, going back to the foundation and seeing what the faculty at Howard really instilled in me to be able to do teaching and provide services.

So, all that, kind of, comes back to wanting to, what is it, the saying, each one teach one? As I learned, I wanted to give. So, with The MECCA Group, it was very important to be an entrepreneur, to be an educator, to be a mental health specialist, to be a parent advocate, you know, especially as a Afro-Latina. I think that was very important to me as I learned about myself, what I wanted to give back to the community.

[00:08:55] Kweli: That’s great. All the same, it's a lot of work to be an entrepreneur on top of university responsibilities and nurturing your own family. What keeps you motivated?

[00:09:04] Dr. Ebanks: My roots, my family, the rich history of Black people. Certainly, the lessons that I've learned from my mother in terms of strong work ethics, you know, being able to provide for her family, really always my very supportive family, encouraging me through the process. But now, as a mother, I would certainly say that my children are the reason why, you know, because again, wanting to leave this earth better than how I found it — so, being able to teach them life lessons, exposing them. And then, also, in terms of what that means for them, because again, it's, it's roots and they continue to branch out and extend. So, being able to model for them and, and also how that looks for their friends and others around them, you know, being active in their school so that other children or other parents or other… it impacts more than just myself and my children.

[00:10:07] Kweli: No, definitely. And I mean, I think, I tell people all the time that don't have children, like, it's one of the hardest things to do is to be a parent. There's so much pressure to get it right. And you're not going to get it right most, well, maybe not, you know, like, half the time, right, it's trial and error.

So, that in and of itself is a huge job. But it also, you know, being a parent gives you a whole nother dimension of understanding when you work with clients and parents in the community trying to help their own youth, right? So, now, thinking about your own… The MECCA Group and the patients that you all see, do you all see a lot of patients with ADHD?

[00:10:38] Dr. Ebanks: We do. We have a number of children, as well as adults, that have ADHD. My history in terms of work experience has been working with children in ADHD and those that were not necessarily diagnosed, you know, initially. I've worked with children at an elite private school in D.C. with children that were between the ages of four to seven. I've worked in home-based settings in Virginia with families, as well as an alternative school in Maryland. And the children exhibited similar behaviors, you know, regardless of their social economic status. However, how it was addressed and how it was treated and how it was cared for was different.

[00:11:23] Kweli: That's key. And we're definitely going to dig more into that. Before we get further into our discussion on the importance of how we frame ADHD and those dynamics, and when we talk about it with youth and their support system, we're going to explore what ADHD is, how it impacts children, generally, as well as illuminate the specific experiences of Black children with ADHD.

So, first, just to, to make sure we're all grounded with a common understanding, what is ADHD?

[00:11:50] Dr. Ebanks: So, ADHD is a disorder that is based on an assessment that can be given by a psychologist, psychiatrist, mental health professional, as well as a pediatrician or physician. And there is a criteria that has to be met. There are certain conditions or behaviors that have to be exhibited for at least six months for an individual to be diagnosed with ADHD. But it is a neuropsychological disorder, meaning that there is a physical as well as neurological in terms of how your brain works and how it triggers certain chemical releases of hormones. And then it also then affects your behaviors, you know. So, as a result, that is why there needs to be an official diagnosis.

And it looks different with everybody because there's different types of ADHD. So, there's different criteria. So, typically, a person would have to exhibit five to six of those behaviors. It could be, you know, inattention. It could be fatigue. It could be hyperactivity. So, it looks differently and exhibited differently in people.

[00:13:09] Kweli: And you noted that there's different types, and I think some people, kind of, get confused because people refer to it as ADD or ADHD, the “H” being the “hyperactivity.” So, could you, kind of, delineate for us what's the difference between ADHD when it's the type without the “H” and then when you have the “H”?

[00:13:25] Dr. Ebanks: Yeah. So, there is one that's predominantly inattentive. So, that means that there's a lot of symptoms of inattention. So, there is a lack of focus, a lack of ability to focus on details, just, kind of, veering off. So, that is the inattentive type. And then there's also predominantly those that are the hyperactive and impulsive, meaning that a person has impulsivity. So, they're very eager and they're quick to do without something telling them to not do and stop. And then they're also very active. They're, kind of, fidgety, you know, not able to, kind of, sit in their seat for a long period of time and not focus again. Kind of, all over the place, as people may say. They're, kind of, all over the place.

[00:14:18] Kweli: And of course, you can also have both.

[00:14:21] Dr. Ebanks: A lot, yeah.

[00:14:22] Kweli: And that's very common, too, that you can be either/or as well. And so, in your experience, how have you seen ADHD generally tend to affect the child's experience?

[00:14:29] Dr. Ebanks: So, it's the focus and attention, you know. Those children that make common errors, let's say repeatedly, even after being corrected. For example, in their homework assignments or in grammar, whether it's math or writing. It certainly can impact their grades because of the fact that they're not paying attention.

So, those simple mistakes that could have been corrected, so that can be the reason why they get it wrong versus right. It could be disruptive in the classroom. Those kids who will raise their hand and call out the answer at the same time. You know, they could be right, but now they're being reprimanded because they called out in class. So, those, often, disturbances. Again, they're, kind of, restless. They're fidgety, not wanting to sit in their seats. They, you know, could be the student who's, kind of, getting up to throw things in the garbage can or, kind of, wanting to go to the bathroom constantly.

And also, they can exhibit signs of being forgetful. So, you tell them something one minute and they forget. So, there's certain, again, techniques. And I wanted to jump into the techniques because, again, it could look differently with every children.

And some of these can be seen as common, you know, children who can be distracted, children that have impulsivity. So, when is it disruptive is when it impacts their grades and impacts their lifestyle. Is this common in all areas of their life? You know, home, as well as school, out in the community, out in, you know, if they're involved in sports and activity. So, if it's just happening in school, it may not be ADHD. And that's why a proper diagnosis is important.

[00:16:18] Kweli: Right, because there might be other things going on in their ecosystem or in their life.

[00:16:22] Dr. Ebanks: Yes.

[00:16:22] Kweli: Does it also have an impact on their own relationships, in their family or with their friends?

[00:16:27] Dr. Ebanks: Yes, again, because of their lack of following directions, kind of, forgetting to do their chores. So, now, they're going to get punished. You know, not wanting to share or not waiting their turn. So, they take something from a sibling. So, it can certainly impact relationships as well. Even in terms of adults, it can impact marriages and relationships with friends or significant others.

[00:16:56] Kweli: Right, no, for sure. And as a parent, I mean, I'm sure the children who don't have ADHD already don't listen. So, this is probably a whole other level.

And you mentioned adults. So, while the focus of our discussion today is on the impact on children, I'd like to, at least, touch on how it continues to impact one into adulthood as well, being that I myself was diagnosed as a child, and I'm still learning how to best navigate this set of characteristics, I like to call it.

Recently, I read that the life expectancy of adults with ADHD is 13 years less than average, right? And that's pretty jarring. That's significant. And this is because we generally seek more stimulating experiences that can be riskier than average, as well as suffer from related issues, like chronic anxiety.

And we're also… we've been found to be 5 to 10 times more likely to become addicted to unhealthy behaviors. Again, related to that, sort of, need for stimulation and not being able to focus.

So, knowing this fact alone, I think can help some adults with ADHD just at least be motivated to better manage themselves or at least to seek help, right? Because again, 13 years, that's, that's significant. So, Dr. Ebanks, can you please give us a brief overview, a little bit more, I guess, of how, if left undiagnosed, especially, how ADHD will show up in adults and, thus, the risk one faces if they mature into adulthood without giving attention to that?

[00:17:58] Dr. Ebanks: So, studies show that at least 60% of children with ADHD can carry it into adulthood. And as a result, there's over more than 8 million adults. That means 4 to 5% of Americans that have ADHD as adults. And it could certainly impact a person's life in terms of employment, their consistency to be able to, you know, get to work on time, complete tasks, complete their responsibilities, their duration at a job, in terms of being, kind of, bored and wanting to go from job to job, you know. That can be certainly impacted.

Also, in terms of their health, because it could certainly impact their hypertension, other physical and medical ailments that can be impacted as a result of their just impulsivity, you know, making bad decisions, a brown food selection. Or, some individuals also end up wanting to self-medicate and not, perhaps, using illegal drugs to, kind of, treat what they have not been properly diagnosed.

So, we're talking about a population of people who have been diagnosed, and then there's a number of people who don't get diagnosed. And therefore, they don't understand what is happening to them, but they're trying to fix it.

[00:19:40] Kweli: Right. And that could even be legal drugs like alcohol, right?

[00:19:43] Dr. Ebanks: Yes.

[00:19:44] Kweli: And becoming alcoholic, I'm sure, is common, unfortunately.

[00:19:47] Dr. Ebanks: Mm-hmm.

[00:19:47] Kweli: I want to get, kind of, more into diagnosis and treatment, and then a little bit into causation in the conversation. So, you talked a little bit about how it's diagnosed in terms of meeting a certain criteria. Can you expand a little more on, if you suspect you or your child has ADHD, like, what would be the next steps towards finding out if, indeed, you really do have it? How do you get diagnosed?

[00:20:07] Dr. Ebanks: So, parents can request an evaluation through their school. So, public schools are required to conduct an evaluation if a parent requested when it's due to reasonable reasons. So, certainly, bringing it to the attention that you're concerned about your child's behavior, their academic performance, and how, perhaps, their behaviors are impacting their academic performance is certainly a reasonable reason.

So, typically, in a school, there's a school psychologist that will conduct an evaluation, psychological assessment, a psychoeducational assessment, or a clinical assessment. And this will typically be a number of tests, subtests. For example, there is… Conners is a very popular one that is used in schools. So, they're rating scales. So, they ask, they get the perspective of children, they get the perspective of parents, and they get the perspective of the teachers as well, because that way you're not only seeing it in one setting. And you want to also value the opinion of the child to see how they see themselves. So, there's a number of questions that are asked. And those are typically… then, there's questionnaires.

It's also very important to do observations. So, to be able to sit in a classroom and see how the child is interacting with others, how they're following directions. And it's best if you're able to monitor the child on more than just one occasion, but just because of the influx of evaluations that most school psychologists have to conduct or administer, there's typically only an opportunity to do one or two observations. But that data, as well as the anecdotal data that is collected, are ways to substantiate whether or not a diagnosis of ADHD is appropriate.

However, that then can lead to special education services through IDEA, the Individual Disability Education Act, requires that children that fit the criteria under 14 different categories to receive services. And ADHD can fall under the category of other health impaired. So, a child can receive special education services for that, as well as if it's not necessarily impacting their grades or their academic performance, also, parents can request a 504 plan.

[00:22:47] Kweli: Right, and that gives them a lot of protection and flexibility. And the school has to comply, right?

[00:22:50] Dr. Ebanks: Yes.

[00:22:53] Kweli: Okay. And so, you mentioned something about how widespread is ADHD, but could you delineate a little more in terms of what we see for children in terms of ethnic groups or other demographics? Is there a difference between diagnosis?

[00:23:05] Dr. Ebanks: Yes. So, unfortunately, the reality is there is, truly, racial disparities when it comes to diagnosis, treatment, services. Children with ADHD receive services, special education services. However, typically, children that are minority children, Black and Brown youth, typically fall under the category of emotionally disturbed.

So, they will get the diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder or having impulsivity and other disorders that are related to their behavior, and not ADHD, because they're, kind of, overlooked or seem to be more of academic disabilities because ADHD is not a learning disability. So, the diagnosis of learning disability is more prevalent with African American children than it is for White children.

[00:24:13] Kweli: And I think we're going to talk more about why that perception may vary, but it sounds like, basically, when they look at what's happening, it's more like you see the symptoms but don't understand it to be part of a larger condition. And therefore, it's not going to get treated properly.

[00:24:26] Dr. Ebanks: Or that's the way they act, you know. So, it is… it's seen as a cultural behavior rather than a medical behavior. So, therefore, it is not… and again, it depends on who's doing the diagnosis and who is doing the… providing the treatment, you know, and who's understanding the child. And that's why it's important to get a proper assessment to really look at the child as a whole and being able to understand what is common and what is, you know, typical for this child rather than just, okay, looking at the child as member of a group or, you know, as a race and what is seen as, oh, that's typical, you know, for that individual.

[00:25:14] Kweli: Right. I think one aspect just to always consider is that, you know, research shows that, when a child has even just one parent with ADHD, they're much more likely to develop it themselves. And so, that being said, have you ever seen a child diagnosis prompt parent evaluations? Or, in other words, when a child has ADHD and they start to look at the symptoms and the parent learns about it, do they ever start to consider, “Well, maybe I also have it?” Has that ever happened? And have you ever seen a parent, kind of, respond and try to manage their own symptoms?

[00:25:44] Dr. Ebanks: I do recall working with a father who said, “Well, I did that. I wasn't diagnosed with ADHD and, kind of, grew out of it.” So, again, because of the fact that, even though this disorder has been around for, you know, many years, it first came about in 1902. You know, it was called different, something different then. And in the 1960s, it was called hyperkinetic disorder. And then in the 1980s, it was then labeled as ADHD. But again, if you look historically, looking at who was doing the evaluations, who were typically the clientele, and who was able to receive the medical coverage for proper treatment, all of that needs to be taken into consideration in terms of why so many African Americans were not diagnosed early on and had to learn how to cope with it and deal with it, so they don't understand, perhaps, why their children are now either being diagnosed with it or understanding why their children can't get over it or learn about it.

[00:26:57] Kweli: So, as mentioned, the key part of The MECCA Group's mission is to serve systems of youth. And this may include families, teachers, and other members of a youth ecosystem. Why is this so important in clinical treatment for children generally, and is it of particular importance in treating ADHD?

[00:27:15] Dr. Ebanks: Any disorder is critical to, to certainly treat. And from it really comes the awareness, truly helping families understand what their children are, are experiencing and then how it impacts the family. Because for a parent to bring their child in for an evaluation or for therapy because they're impulsive and they're making bad decisions and they keep getting in trouble in school, it's difficult for parents to admit that to themselves. That's difficult to ask for help, because they're expected as a parent, as you said earlier, it's the toughest job to do because we're trying to get it right, and we can't always get it right. So, to get that assistance is why we, at The MECCA Group, are here to be able to provide that assistance.

And when we do our evaluations, we are very culturally aware. We train our evaluators. We have trainees. We have licensed individuals, professionals that conduct the evaluation that really see it from a cultural lens, to truly understand how this disorder is being demonstrated by this particular, this specific client and what that looks like.

[00:28:36] Kweli: No, I don't think there's a huge release as a parent to just admitting and realizing, like, “I'm not going to always have it all together. I'm going to make mistakes. And some of the things that my child goes through, their experience, it has nothing to do with me. And it was going to come about whatever decision I made anyhow, right, in particular, maybe with ADHD.”

[00:28:54] Dr. Ebanks: When you look at social media, when you look at what has been discussed in the news and mass media about ADHD, a lot of it is pushed towards medication. And parents don't want to look at medication as the first way of treatment. And that's what they're scared of, having their children look like a zombie under this medication and how that is going to help them. So, education is really key to helping the parents understand what ADHD means.

[00:29:29] Kweli: Right. And I can also understand, even from an identity standpoint, like, the more labels your child has, what is it going to cause to their belief system? But I think that's why the narrative we present, which we'll talk about in a little bit, is so important.

So, you talked a little bit about medication. So, one thing we want to explore is, well, what are the ways ADHD can be treated? And how do you determine what the best treatment plan is for each child?

[00:29:57] Dr. Ebanks: I think the best treatment plan for each child is an individual one. It's not a one-formula-fits-all. You have to look at the lifestyle that the family has in terms of what their beliefs are in terms of holistic medication, what their beliefs are about prescribed Westernized medication. You ask questions about the child's sleep pattern, the child's eating patterns, nutrition. These are all parts of a greater plan to be able to treat the disorder. Again, kind of, a holistic approach. You know, the child's energy level, because again, as we discussed before, there's three different types of ADHD. So, depending on what type of behavior a child is exhibiting, that's what you want to address.

So, you want to look at… there's a lot of vitamins that can be used as supplements to help to treat the disorder besides medication. There's multiple approaches in terms of even therapy. You can use a mindfulness approach. You can use cognitive behavioral therapy. You can use applied behavioral analysis. So, it's a multi-level approach to a big problem. It's not just one solution. Medication is not the only solution.

[00:31:18] Kweli: So, that being said, what is the role of medication? Like, could it be used, kind of, even temporarily to help someone get grounded and, kind of, change their behaviors and practice different things? Does medication work for everyone? Where does that fit in?

[00:31:32] Dr. Ebanks: Again, I'm not a physician, but a psychiatrist and a physician would be… or a pediatrician, would prescribe the medication based on the age, you know, what is appropriate in terms of the height, weight, and all that they use to calculate what is the appropriate medication. And there are the common ones. You know, Ritalin and Adderall, you know, are typically the ones that most, you know, are commonly prescribed. But when it comes to medication, it is a way to stabilize initially so that you can add on these other layers of treatment. It is, kind of, the first step, but it certainly is not the last.

[00:32:16] Kweli: So, while we don't have time to go too much into depth about the cause of ADHD, I think it's worth touching just a bit on some of its psychoneurological basis and associated behaviors to, kind of, help ground us in an understanding of where it's coming from, and again, just scratching the surface. In my own studies, I've looked at the work of psychologist, Dr. Edward Hallowell, who has written several books that helped me really see myself as a young adult, which were very useful in a practical way during my own journey.

In his most recent work, ADHD 2.0, he describes the importance of the balance of two neural networks that we all have. And these networks, though, behave differently for people with ADHD. And there's implications for that, of course. So, the two networks are the TPN and the DMN. So, the TPN is the task positive neural network, and this set of neurons is activated when we need to maintain focus on a single task. And it supports that kind of effort. So, if you're writing a paper, or gardening, or whatever it is, right, you need to stay focused on what you're doing, so that you can really get it done. That's the TPN being activated.

Then there's the DMN, or the default mode network. And this is activated when we're thinking more broadly using our imagination and creativity and trying to see a broader picture and envision what we want to see manifested, etc., right? So, it definitely has an immense value to be able to activate the DMN. But of course, we have to have a balance. And so, the normal situation is that there's what Dr. Hallowell will call a switch that allows a person to toggle from one network to the other as needed, right? So, that makes sense. Sometimes, you need to focus, sometimes you need to think bigger and more broadly.

However, when you have ADHD, they say that that switch is glitchy, right? So, the DMN or the, the one that governs your imagination in this bigger broader picture can often then disrupt the task positive network that you need when you have to be more targeted in your focus, right? So, obviously, we, we know how that plays out, that someone that just can't focus on a single task and just, kind of, keeps daydreaming maybe, right? So, that might be how you see it manifest.

So, this can also cause people with ADHD to get stuck in the task positive network as well, right? So, people with ADHD, we tend to also have moments where we, sort of, “ hyper-focus,” right? So, something that we may be really passionate about and we just get stuck on it and we just can't think of anything else. And that's all there is to it. And so, that's also, kind of, a result of that glitchy switch, not being able to toggle back out of that. So, that does have utility, so we'll talk about that as well. But that's, you know, I think an important aspect to keep in mind.

And there's another book that's been super helpful for me in both having ADHD and addressing ADHD in children, which is Dr. Gabor Maté's book, Scatterbrained: The Origins and Healing of ADHD. He discusses the importance of the prefrontal cortex, which is the part of our brains that controls our decision-making and actions, as well as attention and focus. So, naturally, this is of particular interest when thinking about the general lack of focus that characterizes ADHD.

So, he cites a study of a group of preteen boys with ADHD that compared them with a group that did not have ADHD, in which brain activity was measured using EEGs. So, what they did, at rest, they looked at the EEG output of both groups. And there was no difference in their prefrontal cortex activity. But then, when they had each group engage in reading and art tasks, the electrical activity of the non-ADHD group's prefrontal cortex increased, which makes sense. Their brains were aroused. They needed that to be able to focus and get engaged when something came up. But then the electrical activity for the group with ADHD, for their prefrontal cortex, it actually decreased, which means they become less able to focus and perform, even though the task came up that actually required that electroactivity to increase.

So, when you have ADHD, our brains literally may become less aroused and ready for action when we begin an activity. And I think this is probably even more so true when it's an activity that we're not passionate about. And so, you know, when I read about this, I really reflected on my own experiences in K through 12, as well as undergrad. And I was known for falling asleep in class. Like, if it wasn't a class that I was passionate about or something, a conversation that was very stimulating for me, specifically, I just, kind of, it was, it was over. I was still able to perform pretty well, honestly. And a lot of teachers got surprised that I even retained anything from after class. But I think that really spoke to me, thinking about, like, my brain just, kind of, shut down, shut off.

So, it would have been nice to have, kind of, a framework in education where I could get more movement, perhaps, right? So, Dr. Ebanks, are there any other physiological aspects of ADHD you think we should illustrate here?

[00:37:00] Dr. Ebanks: No, I think what I appreciate about Dr. Maté’s and Dr. Hallowell’s work is that it gives you a different perspective. And I think that's what's important for parents, for individuals who are trying to understand ADHD and how it applies to themselves or their children or, you know, a significant loved one, is to be able to get a different perspective. You know, rather than just saying that it is a neurophysiological disorder, that your brain is not working right, and that you need medication to resolve it, you know, I think it's important to see who is the researchers who are doing the work, who are the participants in the research, because again, unfortunately, when research is done solely by one group on another group that is not a participant in that group, there could certainly be already research bias.

So, I think it's really important to have different perspectives when you're looking at understanding what it is. And that's what I certainly can appreciate. And, you know, it seems as if this helped you, you know, as a person living with ADHD and how that helped you as a parent as well. And I think that's what's important — to have tools and materials available that work for anyone trying to understand this, and that it makes sense to them.

[00:38:38] Kweli: Right. No, and I think it also can help someone with empathy, right, to understand, “Well, hey, there's something different about how the brain is working for this person.” It's not like they're choosing to be disruptive or something. And then it gives you options, too, about how to respond to that difference.

[00:38:57] Dr. Ebanks: And, and to add to that is also that it's not a deficit. It's not a problem. It is something that is special and unique to this individual, and that it could be… it certainly can be beneficial and work to your benefit. You know, once an individual learns how to maintain it and control it, say that it can be part of a superpower, you know, for that person living with ADHD, because there are many successful individuals like yourself that has ADHD, probably, got diagnosed at a later age, and then again, if it was diagnosed sooner, how much more that could have benefited you, could have benefited your teachers, to understanding who you are.

[00:39:42] Kweli: No, definitely. Definitely. And I want to talk a lot more about that as well. I think that's so key. And one other thing just to mention in terms of the potential basis for why ADHD occurs, this, this neurological set of conditions that undergirds ADHD, to answer this question is way beyond the scope of our time today, but I think it's worth touching on this again just briefly, as I think that can really help parents and caregivers, especially of very young children, even people who are considering having children and maybe have ADHD themselves, knowing that their kids are likely to get it as well then. So, in the aforementioned book by Dr. Maté, Scatterbrained, he puts forth a really compelling argument that, more than anything else, this condition is an environmentally induced one, specifically caused by developmental disruptions very early in childhood related to healthy child attachment and attunement to their caregivers.

Now, attachment and attunement can be summed up, in my opinion, as feeling securely connected and cared for enough, so that one can feel confident with independently venturing out. And it's very well known that infant and young child experiences in this area have major implications for their mental and emotional experience for the rest of their lives. According to Dr. Maté, for more sensitive people, such as those that end up with ADHD, even small disruptions to attachment and attunement early on are likely the biggest determinant of a later diagnosis. This means that the more deeply traumatic and consistent one's early childhood experiences are, the more likely they would be to develop the condition or experience more severe symptoms.

He also presents some really great remediations for parents that they can practice to support their children with this in mind. So, I highly recommend this book to anyone with ADHD or anyone who knows someone who has ADHD and has to deal with them, which is probably all of us, whether we're conscious of it or not.

[00:41:32] Outro: Thank you for listening to part one of our discussion about changing the ADHD narrative from deficit to superpower with Dr. Mercedes Ebanks. So far, we've covered the basics about ADHD and how it impacts children. Tune in soon for part two, in which we'll examine the Black youth experience with ADHD, as well as discuss support strategies for parents and teachers to build empowering narratives to support our children. Please, join us.