HU2U Podcast: Changing the ADHD Narrative From Deficit to Superpower (Part 2) feat. Dr. Mercedes Ebanks

In This Episode

ADHD is one of the most commonly diagnosed neurodevelopmental conditions for American youth. Addressing the diagnosis is no easy feat, and there is no one size fits all solution. But an ADHD diagnosis for Black children can be compounded with unique challenges, such as stigmatization, which can negatively impact how others at school and within their communities treat them.

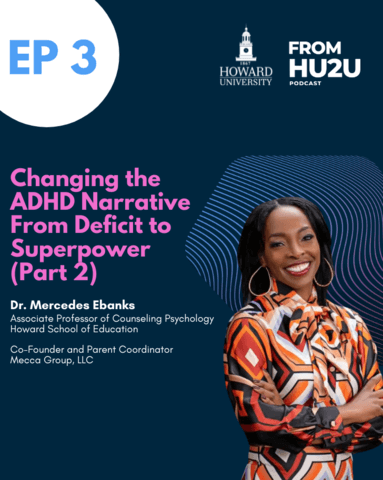

In the 2nd part of this 2-part series, host, Howard alum, and developmental psychologist Dr. Kweli Zukeri continues his conversation on ADHD with guest Dr. Mercedes Ebanks. Dr. Ebanks is a double Howard alum and Associate Professor of Counseling Psychology at the Howard School of Education. She is also a Behavioral Therapist and the Co-Founder and Parent Coordinator of the Mecca Group, LLC.

This episode will delve into the complexities of an ADHD diagnosis in Black American children. We’ll hear about the importance of understanding the cultural and environmental factors that contribute to ADHD symptoms and the potential misinterpretations of these behaviors in educational settings, and the broader societal issues contributing to ADHD symptoms, such as excessive screen time and the lack of representation among Black medical professionals. The conversation also emphasizes the role of parents, teachers, and mental health professionals in recognizing ADHD's potential and developing strength-based approaches to support children.

From HU2U is a production of Howard University and is produced by University FM.

Host: Kweli Zukeri, PhD

Guest: Mercedes Ebanks, PhD

Listen on all major podcast platforms

Title: Changing the ADHD Narrative From Deficit to Superpower (Part 2) feat. Dr. Mercedes Ebanks

Publishing Date: July 16, 2024

[00:00:00] Dr. Ebanks: You want to look at children, kind of, also having that superpower, right? My daughters are Marvel fans. I just saw that movie Madame Web. And she had to learn, like so many of these superheroes, how to control their superpower, you know, because it wasn't innate. They typically overused it or misused it.

And once they learned how to use it, that's when they were the heroes. And I think that's important to help the children to understand that it's not a mistake that they have or a problem that they have. It can certainly be used as a uniqueness that they can use for their benefit.

[00:00:52] Kweli: ADHD is one of the most commonly diagnosed neurodevelopmental conditions for American youth. Addressing the diagnosis is no easy feat, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. An ADHD diagnosis for Black children can be compounded with unique challenges, such as stigmatization, which can negatively impact how others at school and within their communities treat them. In turn, this may cause them to internalize harmful and debilitating beliefs about themselves, which can have devastating consequences.

Despite this, there may also be great potential in ADHD to be tapped for Black children. On today's episode, which is part two of a two-part series, my guest and I will explore this situation, as well as the potential that lies within changing the ADHD narrative and approach from one of deficit to superpower, and how parents and teachers can help their children and students with ADHD both utilize it as a strength and manage its problematic aspects.

Let's dig into it.

Welcome to HU2U, the podcast where we bring today's important topics and stories from Howard University to you. I'm Dr. Kweli Zukeri, Howard alum and developmental psychologist, and today's host. I'm here again with Dr. Mercedes Ebanks, Howard alum and associate professor of counseling psychology at Howard School of Education.

She is also a behavioral therapist and the co-founder and parent coordinator of The MECCA Group, LLC. At the end of part one of this series, I left off noting Dr. Gabor Maté's assertion that experience with early childhood attunement and attachment play a critical role in a youth's development of ADHD. And here, we continue our discussion.

So, if we accept Dr. Maté's premise, then it only makes sense that oppressed communities, such as African Americans, would experience such conditions at higher rates and in, perhaps, unique ways. Like so many things due to a long history of uniquely American multilevel racism, the experience of people of African descent has some distinctions when it comes to ADHD.

There's a great article in our latest Howard Magazine issue of Winter 2024 by Tamara Holmes called Black with ADHD. And I highly recommend anyone to check that out as well to get a great summary. But with that in mind, we're going to talk a little bit more now about the Black experience with ADHD.

And so, I personally believe that one component of the environmental conditions that contribute to overall Black youth trauma are nefarious so-called master narratives that pervade all of our institutions of socialization, including schooling, and which shapes so much of the Black experience in America.

These narratives shape the beliefs all of us have and underlie how White teachers often subconsciously perceive their Black students with bias. For example, a teacher or caretaker may perceive a certain behavior in a White child as benign while perceive the same exact behavior, to your point earlier, in a Black child very differently.

So, Dr. Ebanks, how might this play out when it comes to Black children with ADHD?

[00:03:48] Dr. Ebanks: As you started to state, that the impact of generational trauma and racial trauma on attachment is significant, especially when you look at the African American community. You look at the impact of socioeconomic status in terms of the availability of parents due to work schedules, due to their household dynamics, due to being able to be available for their children, to be able to bond, or can they afford the 16 weeks of maternity leave and how quickly they must have to return back to work to be able to provide the formula to feed their children.

So, that certainly impacts bonding, and bonding is certainly part of that attachment and the impact of, you know, separation anxiety and so many disorders that can be a result of the separation and not being able for parents to be able to be consistent with their parenting behaviors when their child are in need of soothing, in terms of their attention and impulsivity. Unfortunately, we live in a society right now that is a breeding ground for inattention. You know, the number of distractions, the number of disruptions that are constantly being plagued the visual and the sensory stimulation, the overexposure, it's a lot to be able to take in now as well as to manage.

So, if adults are having difficulty with this that are not diagnosed or don't meet all the criteria for ADHD, it certainly can be certainly overwhelming for children, especially when they don't have a strong foundation. And again, the impact of generational trauma and not being able to have, perhaps, being shown or modeled how to cope or how to manage impulsive feelings and in being able to react certainly feeds into why teachers may see the behavior as a cultural difference rather than understanding the root of that cultural difference.

So, it certainly can be a difference in how the behaviors are, are being demonstrated or being showed, but it's not just because we were born with it, you know, in terms of, “This is our impulsivity because we were born.” We had to adapt to it. Giving, and that again, kind of, goes back to the assessment is certainly important, because you want to get the perspective of all.

You know, a child with ADHD has it at school and at home. So, their behaviors are very different at home than in school. It may not be ADHD, but also, you need to have to ask the questions of what is being asked at home, what is being asked at school. There's more to it to truly understand, because are they being asked to focus at home or is it, at home, perhaps, the child is needing to watch TV because the mother or the father has to work or has other, you know, responsibilities and can't give the child the individual attention that is needed? In the school setting, they're distracted because there's 28, 30 other students in the class and they just need help on an assignment. So, they're very eager to want to raise their hand or come up and ask for help.

[00:07:20] Kweli: You know, I think that made me think about the fact that, yeah, that, you know, there are actually cultural differences that educational scholars have seen that impact Black students in school, right? So, one of the things that scholars at Howard have found is that something called verve, right? That African American culture is more lively. There's more movement. There's more louder sounds, right? Like, we get more excited. That's just a part of the culture, which doesn't really fit well within the current educational framework that we have at schools, which is a Eurocentric, Eurocratic educational framework, right? So, there's going to be a cultural difference anyhow, and there's going to be a difference between that and actually having ADHD. But even some people might look at that and say, “Well, he has ADHD,” when it's more just like actually just expressing your culture a little more and it doesn't fit with this environment. So, I think that's another complication to sussing out, you know, is it ADHD or is it just, like, a part of Black culture?

[00:08:12] Dr. Ebanks: Yeah. And I think it's the constraints of the education system, too, because we're saying that the, the world is changing. There's a lot more stimulation that children are receiving on a daily basis. But during the school day, they're still being asked to sit at their desks, sit behind their desks for long periods of time.

So, it's, like, it's in opposition of one another. You know, they're overly stimulated, but in, then, during these periods, you're telling them that they have to sit still. And then if you look at, as you said, like, the cultural differences, wanting to, kind of, have movement as you're learning to have music playing, or whatever the case may be, that, perhaps, the school setting, the, the classroom environment, can, if you make a shift to that and have desks where children can stand, or is it okay if a child stands or is it that they're being disorderly, you know, because they want to just, kind of, really just stretch their legs and stand and do their work? And they're doing their work. We're very restrictive in our school environments.

[00:09:15] Kweli: Right. And it's like more than we can probably really dig into today. But I think, so one thing that Dr. Hallowell does talk about is he's seen many patients over the last two decades that display symptoms of ADHD but don't actually have it. And I think they call it VAST. And he attributes it to this kind of society we have that's so distracted. Because we have devices. It's actually astounding how much much entertainment screen time American youth get. A 2021 Common Sense Media report noted that the daily average for teens was just under 9 hours. And by now, in 2024, that's very likely increased if the recent trajectory is any indication at all. Now, that is a lot.

But if you're ingesting all this media that is not intended to teach you but really intended to stimulate you so you keep watching, then, of course, it's going to lead to, kind of, displaying these symptoms. When you're not so stimulated, you can't really sit still. So, that is a bigger societal issue.

[00:10:12] Dr. Ebanks: And it's the access, too. In, in schools, a lot of the transition happened even before COVID, but COVID certainly changed the direction of how schools function, because children are now on their laptops in the classroom. The teachers are writing on the whiteboards, but the children are not necessarily asked to, kind of, go up to the whiteboards and, kind of, solve the problem because, now, they're sitting behind their computer, you know, solving it on their laptops.

Children are just getting screen time. And because they can finish their assignment and if they have extra time, go on a different website, they're doing that. So, all of that is, again, attributing to more of that screen time. So, it's not having them disconnect from that, that visual aid now that they're using to constantly stimulate them.

[00:11:04] Kweli: Yeah. No, we need much more balance. So, another point is that, you know, research shows that Black people tend to have higher levels of mistrust of the mainstream healthcare industry due to what I believe are very sound historical reasons, really, many of which are noted in author Harriet Washington's seminal book, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, in which she really shows a history of intentional mistreatment of Black people by the medical, what became the medical industry.

And so, we also know that, when Black people have access to Black medical professionals, we see doctors much more often and we experience much better health outcomes as a result. The problem, of course, is that there's a disparity of Black medical professionals and medical mental health professionals as well, right? So, percentage-wise, there's not enough of us serving in these professions relative to the Black percentage of the U.S. population, which is why someone like yourself, Dr. Ebanks, is so important in the practice you opened.

Do these factors affect diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, in your opinion?

[00:12:06] Dr. Ebanks: In the profession of psychology, according to the American Psychological Association, there's only between 4 to 6% of psychologists are Black psychologists. That's a problem. Yeah, that's very small, you know. And yet, things can be overlooked. We're not doing the research. So, if we're not the psychologist, we're not doing the assessments, we're not doing the research, and it's not that we're not available to do it. It’s whether or not even the research is being published and where it's being published. And we have to look at who is doing the research on us. How are they interpreting that data? What is being said about us? You know, what is being believed about us?

So, I think that that is why my business partner and I, we started the, The MECCA Group because of the fact that we certainly wanted to address mental health from, kind of, inward. You know, she is also a Howard alum, Dr. Keisha Mack. She is an African American woman who wanted to provide services to our people, but also in terms of training others. We have a very diverse line of professionals and trainees because we wanted to make sure that, although we don't only service African American or Latino clients, that we see it from a very cultural lens and understanding of people and culture and diversity and history. That's what we do in our treatment. That's what we use in our diagnosis to understand.

[00:13:55] Kweli: And that's, again, I think, just revisiting what you said earlier about studying at Howard, why HBCUs are so important. And myself, as a grad student at Howard in developmental psychology, just realizing that so many students are here not just because they want to get a job or do some studies, but it's like, how is this going to contribute to my community, knowing that there is this disparity, in particular? What research am I doing that's going to help add to the literature and these disparities, to your point, right? So, that's why, to anyone who has any type of question, HBCUs still remain a very, very, very important part of our community and society.

[00:14:31] Dr. Ebanks: I sit on the editor's board for the Journal of Negro Education, which is out of Howard University School of Education. We're the oldest Black journal, educational journal in the country. And this is where many students, many young professionals, get their start in terms of publication because they're not accepted other places. This is why, again, the journal stays and remained and is in control within Howard University, because of the fact that we have a say so of the research that is being published. You know, we're very invested in getting African American researchers published. And this is what is certainly important, you know. And that, again, is another reason why to attend an HBCU is because it's about helping you to understand and about the research, because all of this does stem, like, we're able to be able to speak on this because of the work that's being done in these areas. But we have to be the ones that is administering the evaluations, the research, the tests, looking at the data, analyzing it so that we can have a true objective perspective, but also understanding cultural and diverse aspects of it as well.

[00:15:58] Kweli: Definitely, extremely important. Before we move on, are there any other ways that having ADHD uniquely impacts Black children that you want to mention?

[00:16:08] Dr. Ebanks: Organization, I think it's some of the, of the things that may be, kind of, again, overlooked, is looking at organizational skills. It's looking at how they make friends, how long they keep friends, in terms of looking at relationships. It's how they're able to relax. Some children just, kind of, knock out and fall asleep, or is it that you see that they're able to, kind of, settled themselves down to finally, kind of, doze off.

Being able to, again, whether you're a teacher and an educator in the classroom, or you're a parent, or you're an administrator, being able to see the child and detect what patterns the child is exhibiting, kind of, going back to one of your points in terms of, when you were bored in the classroom and how if it didn't interest you and how they would fall asleep. Look at what piques the child's interest and what gets them excited. Because in my work with working with children, I used ABA (Applied Behavior Analysis) or behavioral therapy, and a reinforcement assessment was important, because I can't offer a child a reward that they're not excited about. Helping them to get some intrinsic motivation, it's important to understand their extrinsic motivation first. What do they buy into? Because again, that's not unheard of to be bored. But what excites you?

And I think, a lot of times there's a focus on why they're not performing well, instead of, where are they performing well? You know, what excites them? What are they doing really well in? Why are they so eager to answer and, kind of, and again, focusing on that?

I say that you want to look at children, kind of, also having that superpower, right? My daughters are Marvel fans. I just saw that movie Madame Web. And she had to learn, like so many of these superheroes, how to control their superpower, you know, because it wasn't innate. It wasn't… they typically overused it or misused it.

And once they learned how to use it, that's when they were the heroes. And I think that's important to help the children to understand that it's not a mistake that they have or a problem that they have. It can certainly be used as a uniqueness that they can use for their benefit.

[00:18:45] Kweli: Right. And so, a lot of people say that's an assets-based approach, right? So, yeah, not shifting to, like, this notion of changing the narrative from deficit to superpower. I just wanted to touch a little bit on my own story. So, when I graduated from undergrad, as many recent grads do, I experienced a quarter life crisis as I tried to figure out what to do with myself. And I really struggled with that. This led to a journey of self-exploration and intentional evolution. And a big part of that journey was obtaining a deep awareness of what having ADHD had meant for me so far, both positive and negative, as well as how I could shape my experience with more intention.

My experience in undergrad, you know, I tended to burn myself out, just doing way too much, putting way too much responsibility with different organizations on top of school, and then being burnt out at the end of every semester. So, trying to figure out, like, why did I keep doing that, now that I have all this time to, like, examine myself.

So, Dr. Hallowell, who I mentioned earlier, emphasizes the great talent and deep capacity for producing awe-inspiring works that people with this set of conditions known as ADHD possess. It's much more likely, of course, that this potential is realized, only if one can manage the challenges of ADHD, would show up differently in each person.

And I have to acknowledge, you know, for myself that I don't think I have ADHD in its most or more severe manifestations. I've had enough privilege to be able to make career and educational choices that I've generally really wanted to embark on and been passionate about. To your point earlier about intrinsic motivation, like, that's allowed me to flourish, right, because I've been doing things I want to actually do.

And not everyone with ADHD may be presented with choices that empower them to move with a sense of purpose, which is such a key ingredient to being “successful,” generally, and in particular for folks with ADHD.

Well, Dr. Ebanks, how important is it? You talked about it a little bit already, but how important is it to have the opportunity to pursue things that are of inherent interest to people with ADHD?

[00:20:39] Dr. Ebanks: And this is no different than anyone else. We want to tap into people's interests to see what they're great at. I don't look at strengths and weaknesses. I look at strengths and areas of growth. So, those other areas of growth are just like anything else. We're not perfect in everything, but we're really good at some things.

And I think that's where we want to, especially for children, because it's a label. And it's a label that has a negative stigma. It's a label that, now, for some for parents or for children, now, they're in special education, right?

[00:21:18] Kweli: Right.

[00:21:18] Dr. Ebanks: So, that it can be seen as uncomfortable. And children, as a result, can lack the confidence. So, I think it's important to, kind of, rebuild that, help them to build that confidence, that they are special because they have this special gift that just needs to be worked on, so that they can use it to the best of their ability because of the fact that their interests are important. Whether they are interested in cars, they could become an engineer that manufactures cars or builds the next Tesla. They can be psychologists. They can be… you know, in preparation for this, I, kind of, Googled celebrities that have ADHD. Simone Biles, Solange Knowles, Will Smith, Will.I.Am, you know, they have ADHD. They're all successful individuals.

[00:22:15] Kweli: It’s great to mention to children, too, to say, “Hey, look at these people and what they've been able to do.” Well, when it comes to speaking with young children with ADHD about their particular way of being… returning to what Dr. Hallowell says, he suggests telling them that they have a Ferrari engine, but yet they only have bicycle brakes, right? And so, they need to build better brakes or there'll be a lot of crashes, to say the least. But that engine, though, is extremely powerful and full of potential, right?

So, this metaphor, I think, makes clear the dual potential of both promise and of peril. And I think it's a good way to explain it to adults, too, honestly. And, you know, personally, I prefer not to refer to this as a disorder, but, like, to your point, a set of characteristics or a way of being that has to be managed and understood. Do you think that these are useful approaches?

[00:23:00] Dr. Ebanks: I certainly think that it's useful. Again, depending on who you're speaking with, in terms of the age, you have to make it applicable to them. What is it that they understand? So, make it applicable to them to understand that their mind and their body is working a lot faster than where they should be going.

So, sometimes you, kind of, have to slow your pace to get to that same destination. We're going to get there. But when you get there, you have to be ready for it. Especially with children, you want to speak greatness into them. You want to certainly encourage them. I think the words that we use is very important because they remember that. You know, they remember how a person makes them feel. You know, Maya Angelou, I don't want to quote her verbatim, but she speaks of that. Like, she… you, you will remember how someone made you feel. And I think that's very important. So, the words that we use, helping children understand and be very aware of their body, their senses, their abilities, I think, is very important.

And to teach children the how to communicate that. If that's communicating through motion and physical activity, through dance, through sports, however they need to communicate. It could be through art. It certainly is a way to communicate their talent. And this is all it is. It is a gift that was given to them that needs to just be honed in.

[00:24:29] Kweli: Right, certainly. And so, we talked about this parallel to having a superpower. And in most movies and shows, characters with emerging superpowers first waken to their raw potential, and that's often accompanied by unintentional harm to themself and others. And then they, kind of, undergo a process of self-awareness and management, which is often supported by someone else, like a teacher.

And it's never-ending, this process of refinement, just like in real life, in order to gain control and make best use of this power. So, I think, for me, the question becomes, if you're given a choice, are you going to end up like the movie character, Hancock? You mentioned Will Smith earlier, who played Hancock, who was, well, you all have probably seen the movie, or if not, look it up. But this superhero that just did not realize his own potential and became a menace to himself and others. Or, like, T'Challa, right, who's probably one of the highest self-realized individuals in the media, the Black Panther, played by Chadwick Boseman — may he rest in power, also, a Howard alum, we're very proud of — who became really a ruler of his own destiny and that of his nation, a righteous ruler, right? And I think those are the two kinds of opposite ends of that spectrum.

And one example of, maybe, a characteristic that might be both a superpower but also really be a something a challenge to manage is this ability, I would say, to be able to multitask. And then, you know, a lot of people say multitasking doesn't really exist. You can't put your focus and two things at once, but you can bounce back and forth, though. And a lot of people do do that. I think, for me, at least, like, I'm able to do that pretty effectively, and it's been a strength for me, and it has helped me in a lot of things in my life. But then, it's also been a detriment because then I tend to try to do too much, put too much responsibility on myself. So, I've had to learn to say no and not, you know, not, not do everything, right?

But I think that characteristic that can be both a strength and a weakness is why a lot of entrepreneurs out there have ADHD and are able to be an entrepreneur because it requires being able to do so many things. Even if you're not the expert in all these things, you have to be able to address finances, operations, development of the product, etc., and put all that together. That takes a certain skill set. So, we do see a lot of entrepreneurs that have ADHD. You yourself are an entrepreneur. To my knowledge, you don't have ADHD.

[00:26:42] Dr. Ebanks: I think I do.

[00:26:43] Kweli: But you understand entrepreneurship. Maybe, you do, right? Well, do you think ADHD is, therefore, an asset when it comes to entrepreneurship? And I know you are actually doing research, if you want to tell us a little bit about it, on entrepreneurship.

[00:26:53] Dr. Ebanks: Yes, I agree that we have to multitask. You know, I said earlier that we are a breeding ground now, certainly, of inattention. We went from five channels to 500 channels, you know. I remember growing up and only having a few channels to dial, you know. Now, your remote goes up to 1,000 in terms of channels.

So, you know, because of that, we are constantly balancing as a parent, as an entrepreneur, as an educator, doing all of this and not just one for myself. And this is why sometimes, even when I started studying psychology, I was like, “Okay,” you know, we do this thing about self-diagnosis, but I never put the label on me. I never did the assessment, because I was like, again, “I don't have that. I don't have that.”

But if I truly sat down and, kind of, checked off, I probably do. But again, as you said, you, kind of, learned how to work it to your benefit. And going back to your question, entrepreneurs do have to balance so much. If you are employing other people, you are responsible for their livelihood. They're successful. A lot of pressure you put on yourself to be able to maintain the business, because again, you have a business for a purpose. You have a business for a reason. And because of that, you have to make sure that you are seeing all. Your hands are in everything. So, now, you have multiple hands. Your, your every finger is being used. Every hand, every ligament is being extended because you want to make sure that you are in charge. And because of that, our minds are on different things, whether it's production, whether it's service, whether it's in marketing, whether it's in the finances, so that you can be successful.

And, and that can become, you know, again, very stressful for an individual, for an entrepreneur, and could be the reason that some businesses are not successful, because again, if they were not understanding how much of themselves they had to give in all of these areas and not being able to have the skills to know how to do it, it can certainly become overwhelming.

[00:29:17] Kweli: Right. And just because you can put your attention on many different things at once doesn't mean you're going to do it well either, or manage it well. So, that has to be intentional.

[00:29:25] Dr. Ebanks: And may I add to that, is that, when you are an adult, perhaps, with ADHD or without ADHD, and you are multitasking, and then you have a child with ADHD, you have to look at what you're modeling. Because if they see that you're multitasking, you're not being attentive, and now you're asking them to pay attention. It's like, “You’re not doing it.” So, I think it's, again, it, kind of, goes back to modeling and showing children and being able to do the techniques, you know, the relaxation times. How are you, kind of, self-soothing? Teaching children, as you are multitasking, to also teach them the other things that you're doing to, kind of, combat. What organizational skills are you exhibiting to let them know how you're combating the multiple things that you have to attend to?

[00:30:18] Kweli: Okay. No, definitely. And so, that being said, what advice do you have for parents whose children have ADHD? How can they help their children mitigate the challenges and limitations while, also, simultaneously, enhancing the strengths and potential that accompany it?

[00:30:34] Dr. Ebanks: I think it's helping your children to be self-reflective and to identify their feelings, being either overwhelmed or overstimulated. Helping them to monitor that. Also, it's really basic, is the communication. I think helping children to communicate how they're feeling is important. I think that's the first. Talking to them about how their feelings or what their experience is like with the inattention. Is it affecting them in the classroom? Or, how they're using it for “good,” right? So, I think that's very important, is to, to help their children to understand what is going on.

Awareness is key. Again, very essential to be aware. I think, also, to provide support around that, that's beyond you as a parent. Helping them to be around other kids that may have that, so, maybe, perhaps, depending on how young they are, play therapy, social skills group, psychoeducational group for the children to participate in, helping them to understand, maybe, why sports or dance is important because of the fact that it helps to exert some of that extra energy that they may be feeling, how to help them focus on details, whether or not it's using sensory stimulation through work with occupational therapists or, perhaps, physical therapists.

But I think other services, you know, because a parent can't do it alone. They certainly need a village of people, of professionals that can help them, whether it's going to family therapy or having their children go to therapy, as well as the parents to, perhaps, also find support for themselves, whether it's through Facebook, finding a social group through Facebook, or there's one also called CHADD (Children and Adults with Attention Hyperactivity Disorder). They offer a number of literature and articles, as well as resources, for individuals with ADHD. And for, again, kind of, going back to looking for Black professionals, there's a group called ADHD Black Professional Alliance. So, these are all resources for parents to help them to understand and how to help their children.

[00:33:08] Kweli: Oh, certainly, that's really helpful. Especially the support groups, I think it really helps when you, as a parent period, when you talk to other parents about what you're going through and what you're experiencing and get advice and you realize you're not on your own. Other people are experiencing that, too. And then you get advice from other people's experiences.

And I think, for me, some of the things that I've seen really helped me and, and I've, you know, seen reflected in literature is exercise and activity is so important. Not just staying seated all day, but getting up and moving as a part of that activity. For me, martial arts has been huge because it's a certain level of intensity that I think I need without getting into competing or anything dangerous. But, like, you know, I think so, for some children, you might even say like, “What kind of sports do you need to help you get that intensity while still being safe?” Because then you might seek that intensity in a different way that's unsafe.

And then, like, to your point about mindfulness, you know, there's so many ways you can do, yoga, there's Tai Chi, there's meditation, there's other forms of getting into a meditative state. But I think, yeah, that really is a big part of that awareness. Practicing, all of us, not just people with ADHD, practicing to form the skill of being able to be still at times, you know, it's a skill. It's not just… we don't just have that necessarily.

[00:34:22] Dr. Ebanks: Yeah, that's key. And I'm glad because that was on my note to say, is to be present, put down that technology and be very present with the time, but being still and growing that. So, it could be two minutes and then grow into five minutes. And also, for parents is not to just tell the child to go do it, but do it with them, you know.

[00:34:45] Kweli: Modeling, right.

[00:34:46] Dr. Ebanks: Yes, kind of, do it because the parent needs it. You know, if you have a child with ADHD, it can be exhausting for the parent, you know, as well. So, they're exerting a lot more energy and attention, also. So, to, kind of, be still together and being able to be present, put down the technology, put down the cooking for five minutes, as the food is simmering on the pot, to just, kind of, sit in the living room or sit on the deck or whatever area in your home and sit in stillness and learn to incorporate that, not on a once a week, but as often as possible. And it's, again, I think it's being patient with one another, you know, patient with that child, the child to be patient with the parent. And be patient with time, because it's not an overnight fix.

As I work with families in their home, I would certainly let them know, “This is no guarantee. I'm here to help you to work with your child so we can reduce the number of times that they may have a behavioral, you know, episode or an impulsive act. But it's not going to be a quick fix.” And I think that is certainly key for all parties involved. Teachers, to not understand that just because the school psychologist came in, evaluated the child, now the child has a behavior plan, that it's going to be an overnight success. It's not. It takes a lot of time. It takes investment, you know, by all parties. And I know that parents, teachers, they're there because they want to be invested in the child and, and help the child to learn to be invested in themselves, kind of, going back to that, that growth of that intrinsic motivation.

[00:36:33] Kweli: No, certainly. So, do you have advice, specifically, and a lot of this probably overlaps, too, but do you have advice for caretakers and teachers who inevitably are going to deal with students or youth that they have to take care of that have ADHD? Do you have advice for them to help, for them to help their, the youth that they deal with?

[00:36:54] Dr. Ebanks: It's a culmination of all that we discussed. I think it's to keep the conversation going, to educate themselves, try different techniques, because it's not a formula to fix every child that you are presented with with ADHD. A teacher may have one student this year that looks very different than the child they did last year. Or, they may have two or three children in the classroom that have ADHD and they all need a different approach, a different reinforcement, a different… so, it will need… take time again. And I think that that's important to, kind of, keep in mind that it's developmental. These children are going through developmental stages in their life.

And with that, it's helping them to understand this superpower, if we want to say that, and how to use it effectively with the stage that they're in. How it looked when you or a child in eighth grade, it's going to look very different than how it is when they're in college, or they're graduating with their doctorate, and how they can continue to use it. Because children can grow out of ADHD. However, based on research, it's a small percentage of children that grow out of it. But again, looking at that whole holistic approach, what all has been done consistently.

And it takes trial and error, you know. It's not, okay, this worked and it's going to work forever. You know, children change their interests. Children change their desires. The plan is changed. The dynamics of who is able to deliver the services can certainly change, and that can certainly impact how a child walks away with what they're dealing with.

[00:38:49] Kweli: Certainly, no, those are great, great points. And I think hearing that will help a lot of parents and teachers. I think one of the key points, like you said, is consistency and not forgetting about it, but keep continuing to address it as it unfolds.

So, just the last point I wanted to ask you about today. You know, the central theme of our discussion has been about dismantling false and debilitating narratives and then intentionally constructing positive and affirming ones for children that have ADHD. As noted, I think this is of particular importance for Black children, generally, since there's so many stigmatizations and negative narratives that they face already. In my own doctoral research, you know, I examined the impact of instilling in Black high school students an awareness of and connection to their African heritage. And I found that, in my study, it boosted their racial and cultural identity and, in turn, supported their confidence in academic achievement.

And I haven't seen this applied in, in an ADHD kind of setting to say, what could this same approach do for children with ADHD? But do you think this type of cultural socialization for children with ADHD, in particular, for Black children with ADHD, in particular, could be an extra boost for gaining some sense of grounding?

[00:40:01] Dr. Ebanks: Yeah, I certainly support that idea from that perspective, in terms of cultural socialization. I think that's in, kind of, going back to throughout this conversation, is really understanding culture, really understanding how it impacts all that we do, understanding who we are, understanding our history, and what that looks like, so that it doesn't have children see it again as a problem, you know. I think that that's, you know, is important that we have to change the trajectory of this conversation as ADHD as such a problem that children are facing or as a deficit, but more as how it could be used as a tool to help them to succeed in life. It's because it's just learning how to manage it, learning how to address their attention or their impulsivity to make it something effective for their future, you know. And I think that that's certainly important to have, again, the conversation around, you know, how culture, you know, socialization around this topic is important for children to understand it.

[00:41:31] Kweli: Certainly. So, Dr. Ebanks, you've shared a wealth of knowledge and insight from your experiences with me today. So, I really appreciate it. And I think anyone listening into this episode will greatly benefit as well. Is there anything else you want to add before we close out?

[00:41:48] Dr. Ebanks: I view the NAACP Image Awards and the young lady extremely gifted, Amanda Gorman, spoke of her diagnosis, even though it wasn't ADHD. But she spoke of her diagnosis as speech and language disorder as a child. And now, you see her today delivering a poem at the White House Presidential Inauguration to now receiving a NAACP Presidential Award.

And it's just to get to show that what is considered a disorder doesn't have to stop you. We can excel at anything. And to, to have that support, whether it was her family, her mother, her, her teachers, the services that she received, she received speech and language services, the same way a child may need to receive applied behavior analysis or behavior therapy around this, that it doesn't have to stop anyone from succeeding. I think that the conversation doesn't need to stop here. I certainly appreciate being able to talk about this on HU2U for the Howard Magazine to discuss this topic on the winter edition, where the new president of Howard University was on the cover, because it's an important topic, you know, that doesn't need to, kind of, go away.

This is certainly going to, just as children and adults live this with a lifetime, and it needs to be constantly discussed, because children and adults should not face this to be ashamed or embarrassed, but more to understand it. So, to talk about their successes with it. And I think that's important. So, I certainly appreciate the opportunity to speak on this very important and relevant topic today.

[00:43:39] Kweli: And to your point, I think a lot of successful people can point to the challenges they face as actually setting them up to become that very successful person they became. And in the case of her, it's very clear, speech. You know, speech issue led to being this huge poet that's internationally recognized.

One other thing before we close, for people looking for mental health treatment or mental health support, how can they find The MECCA Group?

[00:44:06] Dr. Ebanks: We are at themeccagroupllc.com. You can find our website. We also have an Instagram page, as well as a Facebook. Find us on YouTube. We did a series called MECCA Moments where we tackled a number of different topics and issues for a good, quite a few sessions online that you can find. But certainly, contact us at our office at 202-529-3117. Certainly, feel free to contact The MECCA Group.

[00:44:40] Kweli: Okay, sounds good. Thanks for sharing, and thanks so much for being on the show today. And as we always end our episodes, HU!

[00:44:49] Dr. Ebanks: You know!

[00:44:50] Kweli: Peace!